Investment Evaluation Process

When it comes to screening out investments, I am as ruthless as an assassin. On this point I have several suggestions:

Understand your circle of competence

I discuss this earlier in this Substack.

Know your resonance points

This gets down to given your investment style, for instance which stage of a company’s life cycle is an appropriate investment. I spent my career in IT technologies, but I eschew tech investments for a number of reasons: (1) I am lousy at picking winners early in their life cycle, (2) too crowded—everyone is looking for the next Facebook and pushing valuations sky high, and (3) I like companies at a later stage with stable predictable cash flows. I may miss the next Google, but I will also avoid the next FTX or Theranos.

Channel your inner assassin

Have your own investment qualification framework. Ruthlessly discard the junk.

Investment qualification comes the down to (1) relentlessly eliminating leads that don’t fit your investment criteria and (2) having the patience to wait for the right opportunity. The objective is to invest in only truly exceptional companies and pay a price that has a margin of safety. Charlie Munger likens it to waiting along the banks of a stream with a spear, waiting for the right fish to come along.

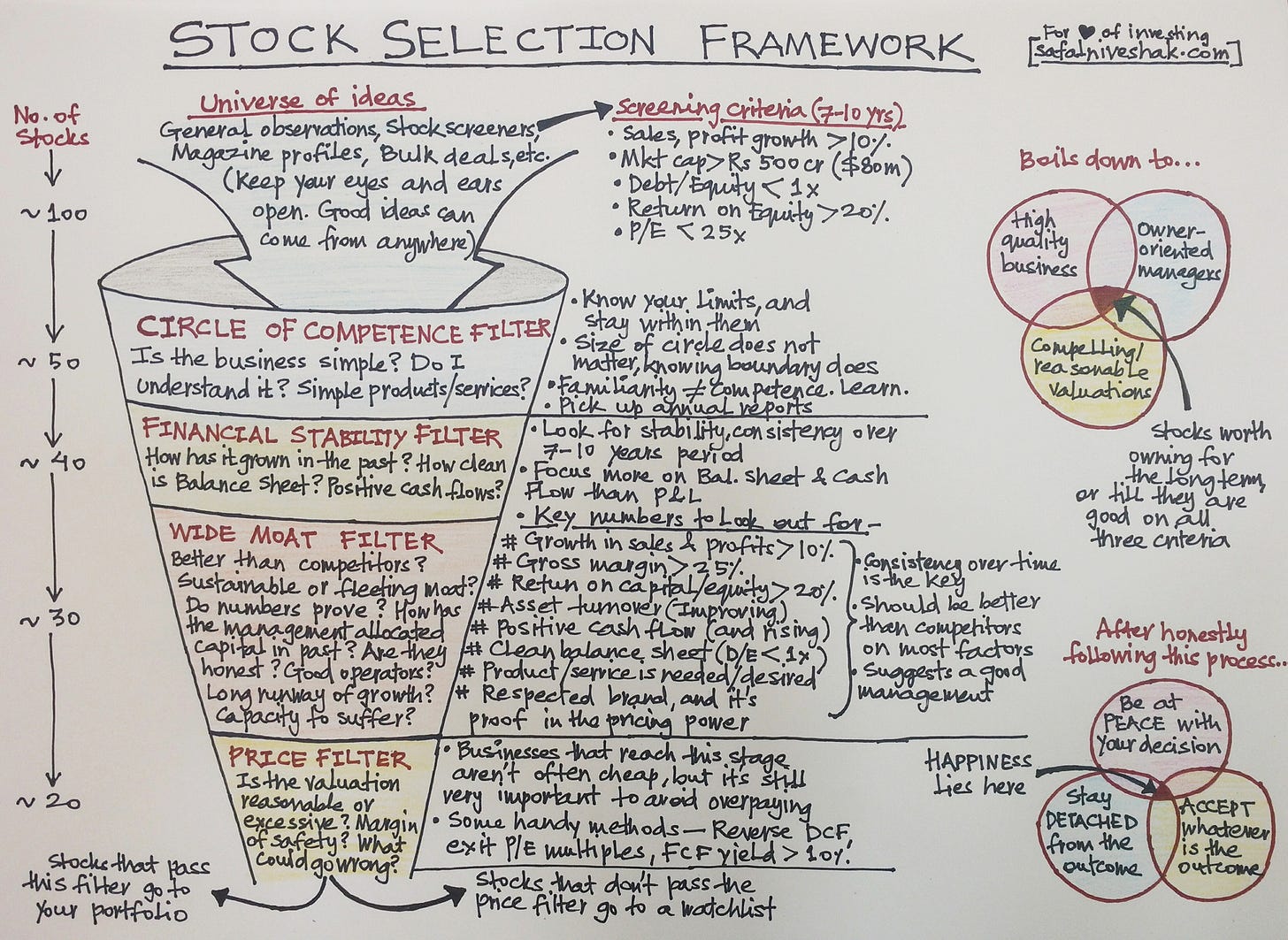

One approach is to have an investment funnel. Readers with sales experience may be familiar with the concept of a deal funnel. The unwashed masses enter the wide mouth of the funnel, and the closed business comes out the bottom neck of the funnel. Deals “fall out” for any number of reasons: customer’s needs are a poor fit with your company’s capabilities, customer has a lack of budget, there is a change of management, you lose to competition, etc.

This funnel metaphor is also great framework for evaluating investment opportunities. Safel Niveshak, an investment blogger has a great stock selection framework shown here:

At first, his graphic may be overwhelming, but focus on major filters from top to bottom:

Circle of competence

Financial Stability

Wide Moat

Price

I won’t repeat his blog. He does a great job of articulating his process here.

In evaluating potential investments, here is some of what I do:

Screen out the junk. I screen based on my inclusion criteria (e.g. high ROC) and exclusion criteria (e.g. dual class stocks). Screening is based on my criteria, some of which I have discussed above.

Read the 10K. The essential question my mind: Is this a company I would ever want to own? Or is it like Uhaul?

Look at competitive companies. On occasion, I will identify a company, only to discover there are stronger competitors than my initial lead, e.g. Foot Locker versus Ross Stores as I discuss above. Companies with sustainable competitive advantages always have superior economics and most often have dominant market positions.

I often look at employee reviews on Glassdoor. This can give an insider’s view on things. Glassdoor reviews can often be bi-modal: love-em or hate-em. Dispassionate employees don’t bother to write reviews.

On this point, I have dodged a couple of bullets by reading employee reviews. One bank in the mid-south, run by a fellow and his wife, had a toxic work environment based on fear and loathing. In another case, I was mystified by a medical device manufacturer in the Mountain States had never pierced $80M in revenue over 15 years, despite a massive total available market. It turns out the CEO was a control freak who could not scale, and had not built a management team. In cases like this, the CEO can, at best, recruit only the c-team. It takes a strong leader to attract strong talent.

No-go investment decisions can come quickly. However, I rarely get to a decisive go decision immediately. I am inherently an impatient person, and my go-slow has become a learned behavior.

Feeling inclined to make an investment and feeling compelled to invest now are not the same thing. Some of my options are:

1. Not now because of a corporate event.

For instance, in 2021 Organon spun out of Merck, but had limited operating history as an independent company. I am a “wash, rinse, and repeat” investor who likes certainty in corporate operations—a proven business, consistent operating history etc. Organon lacked a long track record as an independent company. I put it on a watch list to review in 2022.

Now, bear with me as I go on a bit of a rant.

In 2022, I took Organon off my list completely. When Merck spun Organon out in 2021, it was saddled with massive debt. I should have figured this out when I first reviewed Organon, but I failed to do so.

Loading up a spin-out with bone-crushing long-term debt is a neat trick of most parent companies.

The play-book is as as follows: prior to spin-out the subsidiary takes on a huge amount of non-recourse debt—debt that cannot revert to the parent. The parent moves this cash to the parent as a dividend. The dividend may be an internal dividend and not necessarily paid to stockholders of the parent company.

The parent spins out the subsidiary with bone-crushing debt. The new spin-out now spends the next twenty years getting out from behind the 8-ball.

My issue is that the spin-out did not benefit from the debt in the form of new investments. This is an exercise in pillaging. It is all legal, because it has been fully disclosed in the appropriate filings, which 99% of investors don’t bother to read.

Figuratively speaking, if you want to be saddled with paying child support for someone else’s kid, by my guest. I just move on to my next investment lead.

2. Not now because of an external event.

I mentioned Ross Stores and the Covid shutdown earlier.

3. Not now because of an external condition.

For example, buying an auto manufacturer at the top of the economic cycle is a recipe for disappointment.

Another example is when I looked at banks in 2021 and 2022. I felt uncomfortable that the economy was at the wrong part of the interest rate cycle. Given that interest rates Fed fund rates were at 0, all interest rates had to rise.

My sense is that rising interest rates would be problematic to the operations of the banks. For two reasons: (1) banks that kept long-term loans on their books would see the value of these assets crash, (2) banks that sold their loans generally make their revenue based on transaction fees (e.g. points). With rising rates, transactions would fall, and the bank revenue would plummet.

I was not prescient enough to anticipate the Silicon Valley Bank meltdown, which hinged on a mismatch between the maturity of their assets and liabilities.

4. Love it, but the company is too expensive; price relative to value offers no margin of safety.

Watch Lists

Assuming my qualified stock gets through my maze, I proceed to do a DCF valuation on the company. Aswath Damodaran’s teachings have been instrumental in my nut-and-bolts evaluation. Sometimes the stock price is too close to the intrinsic value—insufficient margin of safety—at which point I put the stock into a watchlist I have created on Google Sheets. My Google sheets will trigger a notification if the stock comes into my price range.

I have a second watch list, which is time driven. For example, for Organon mentioned above I created a follow up date (about a year out) to re-evaluate the situation.

The mouth of my deal-funnel is very wide, with a high amount of attrition between initial awareness and initial investment. I am sure with my approach there are a lot of errors of omission (false negatives), and many stocks get away. In one sense, I don’t care because I only need ten to fifteen investments to meet my objective.

I am looking for GARP (growth at a reasonable price) compounders which I can hold for a very long time. I have had my longest holdings since 1994. Most investments may be two or three years old.

Pulling the Trigger

The previous section gives my perspective on what to buy—or more importantly about what to avoid. This section is about when to buy.

For me it’s a judgement call. I don’t have a codified algorithm on when to make an initial investment. However, as I have said before, I am a Goldilocks investor. I buy only if the planets align. Often I will kick an interesting candidate down the road with a “not now” prognosis.

As an individual investor I am not under pressure to “put cash to work,” and I don’t need hundreds of investments—just a dozen or so boring companies with not so boring economics. To paraphrase Peter Lynch,

Invest in businesses any idiot could run because someday one will.

Come to think of it, I need to call Peter for my next job opportunity.

As I have said before, I have sniffed at Ross Stores for years, but never invested—because of the price relative to the value. If you look at their stock price for the past thirty years, you can see why I really do need to call Peter.

Determining a Company’s Value

For value investors, ascertaining the (net present) value of a company entails assessing the amount of resources available to investors after the company meets its obligations and requirements for the future of the business.

Think about it this way: how much moola is left over for the owners. Note: this is not reported earnings.

To figure out the value, Buffett promotes a concept he calls ‘owner earnings’ and states this as:

These represent (a) reported earnings plus (b) depreciation, depletion, amortization, and certain other non-cash charges ... less (c) the average annual amount of capitalized expenditures for plant and equipment, etc. that the business requires to fully maintain its long-term competitive position and its unit volume.

Let’s tease that apart:

· Start with: Reported earnings are just that, net earnings in the income statement.

· Add: Depreciation, depletion, and amortization appear from the cash flow statement. These are “recoveries” from previous significant investments, called capital expenditures. These are added because the cash went out the door years ago when the company paid for the factory, but since depreciation, depletion and amortization are reported as expenses, they provide tax relief.

· Subtract: the average amount of capitalized expenditures. This is real cash the company has to invest to build new factories and replace worn-out equipment.

Damodaran and others add models to taken into account incremental working capital needs.

Explaining incremental working capital requires a sidebar discussion.

Think of working capital as the money the company needs sloshing around the system for day-to-day operations. A manufacturing company buys inputs, puts the inputs though a manufacturing process, puts the finished product in inventory, waits for an order, ships the product to the customer and then waits for customer payment. It turns out the tooth fairy doesn’t provide the money to make that happen.

As companies expand, their working capital needs grow just as it takes more to feed a growing teenager versus a growing baby. Both may be be growing at the same percentage rate, but the amount of additional food is vastly different. Changes in working capital capture this effect for companies.

Over the past twenty years, analysts have promulgated a metric called the cash conversion cycle (CCC) to capture the effect and normalize working capital to sales. CCC is very useful because it is a ratio and allows us to compare Intel to 3M to Sam’s Cigar stand. CCC is the time in days it takes for a company to go from cash, through the entire production, sales, and collection cycle and get back to cash. Look at Investopedia to get a definition of the inputs into the cash conversion cycle calculation.

The cash conversion cycle is also happens to be good indicator a company’s power, both upstream with vendors and downstream with customers. CCC may be an indication of a sustainable competitive advantage. An old line steel manufacturer with no upstream or downstream leverage may have a cash conversion cycle of 200 days. Such a a company has poor leverage with customers who have many substitute choices.

Often large companies bully their vendors by negotiating long payment terms, e.g. 120 days or longer. However, the company collects from it customers very quickly. This vastly reduces working capital needs—at the expense of both vendors and customers. Only companies with vast market power can get away with this by browbeating both vendors and customers into submission.

In fact some companies—for example Apple, Dell, and Amazon—have a negative cash conversion cycle: their customers pay them immediately (with a credit card) and they pay their vendors on extended (e.g. 120 day) terms. This has the effect of creating a lot of excess cash that, in theory, can be distributed to investors. Sound good?

Not so fast. These are liabilities, and current liabilities as well. Vendor financing is to manufacturing companies what float is to insurers. At some point—for instance when sales taper off—the chickens come home to roost. With falling sales, the cash outflow accelerates and can create a liquidity crunch. Beware of this phenomenon.

Discounted Cash Flow

Aswath Damodaran, the NYU finance professor, has developed the scaffolding I use to reduce my valuations to practice.

The core of the analysis is called a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) evaluation. Instrumental to any DCF evaluation is calculating the net present value of future cash flows. What the heck is that?

DCF is a framework for converting potential future cash flows (in or out) to a value today (or a future value). It is an attempt to equate cash coming in and out in the future with cash coming in and out today.

Think of it this way.

If you have a child born today, how much money will you need to fund his future college education? For instance, suppose you had sufficient resources to set aside the amount on the day junior was born: you have a pile of money that is going to grow over the next 18 years to fund college. Figuring out that number requires making a number of assumptions:

What is the cost of one year of junior’s future college today? NC State is a lot less than Harvard.

How much will costs increase up over the next 18 years?

How long will your kid be in college? Is he going to go to community college for two years and then a full college for the next two? Conversely, is he going to be on the six-year program at an expensive private college majoring in cannabis sampling?

If you don’t have the full amount the day junior is born, when do you invest your money and in what increments? Hint: To capture the power of compounding do as much as you can afford early on.

What is your expected investment return?

What about the taxes on your investment gains?

All of those factors determine how much money you need to fund your child’s future college expense.

Assuming you started with a specific amount today (your “down payment”) and then committed to periodic contributions, how much do you need to contribute and how often to have a target amount when junior matriculates to college?

The DCF calculation for valuing an investment is a variation of this movie run in reverse. DCF figures out given a certain cash flowing into the company over the next period (e.g. 10 years), how much is the company worth today? We call that assessment value.

A company’s market capitalization is the current share price multiplied by the the number of shares. That is called pricing, and may be completely disconnected from value—like Tulip Mania. Compare value and pricing and if value exceeds pricing, you may have a bargain.

DCF is a general analytical frame work to compare the current value of the asset against future cash flows.

Financial analysts do this financial calculation all the time to look at the relationships between current value and future cash flows. They are two sides of the same coin, tied to each other by the underlying assumptions of the DCF model.

Examples: (1) pricing annuities (2) determining pensions resources needed for future obligations, (3) determining how much to charge for a life insurance policy, and the like.

DCF calculations are also used to figure lump sum payments for lottery winners.

We have all heard the story about how “Joe the Plumber” won $20M in the lottery. The screaming newspaper headlines notwithstanding, it turns out Joe did not win $20M. What he won was a cash flow of $2M per year for the next 10 years. The $2M payment in year ten is worth much less than $2M today because of nine years of inflation, or alternatively, because Joe did not earn interest on the money during these nine years.

Winners who take a lump-sum payment get a lot less than $20 million. Obviously taxes are one factor, but the other factor is the time value of money. DCF calculations help reconcile these two different cash flows.

One key point is this: Joe’s lottery ticket has a very different value than a company with identical cash flows of $2M per year for ten years—because at the end of year 10, Joe’s lottery ticket is worthless, and the company has value (called terminal value) as an ongoing enterprise.

To value a company, one needs to do the inverse of this: look at the future owner earnings to determine the present value (actually a variation called net present value). Only then can you determine the value of a share of stock and compare it to its current price. How much are those future cash flows worth given the company’s cost of capital?

Is Wall Street trying to sell you a $200,000 value house for $500,000? After all, someone has to pay for your stockbroker’s Jimmy Choo glasses and his spinning bow ties. In case I haven’t made my point: Wall Street wasn’t built on winners.

The best way to estimate net present value is to use a financial model. Financial models are only as good as the thinking and assumptions behind them. If you are convinced your investments are going to skyrocket like Amazon did in the 2010s, you probably need only $2.32 to fund junior’s college.

Aswath Damodaran, the NYU finance professor, is the go-to guy for figuring this out. He has developed a number of models. However, using a model is like driving a car: you need to know what you are doing before turn yourself loose.

Take Damodaran’s online MBA valuation course. His course steps through the process and he has downloadable spreadsheets which are phenomenal templates for doing your own analysis.

There are other simpler DCF models online, and you might want to start with these, even though they are limited. Damodaran’s are much more nuanced, and through his online courses and other materials you will be able to navigate various corner cases, such handling convertible debt or companies operating in multiple currencies.

One of my pet peeves about DCF analyses is the terminal value. The term “terminal value” sounds like a bad Arnold Schwarzenegger sequel but it’s not. It is the residual value of the company after the analysis period, typically the next ten years. The problem with our analysis is that the terminal value creates a huge swing factor in the valuation of your potential investment.

Here’s the concept. Valuation models typically look at owner earnings for a ten-year period and discount the cash flows back based on the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), hurdle rate, or some other threshold. Recall this threshold answers the question, “What is it worth for me to even bother with this investment?” Recall our objective is to find investments where the return on capital exceeds the WACC . The value during the ten-year period is determined by the extent to which ROC exceeds WACC (as a percentage) and the the amount of excess cash in dollars that the business is throwing off.

The other major component—indeed the determinant—of the valuation is the terminal value of the firm after year 10. Unlike Joe the Plumber where his lottery winnings are worthless past year 10, the ongoing company has real value. The question is: how much?

For their terminal value, most DCF models use a thing called the Gordon Growth Model. I won’t go into the specific rationale behind it. Look it up on Investopedia.

The mechanics are to take year 11 “owner earnings” and divide them by the difference between to the cost of equity (r) and the perpetual growth rate of dividends (g). (Take this on faith.)

Here is a tangible example to show the swing factor of the terminal value;

Example 1:

Year 11 owner earnings $100.

Cost of Equity = 6%

Growth Rate = 1%

Terminal value: $100/ (.06-.01) = $100/5% = $100 * 20 = $2000

The 5% denominator bolded in the equation above is called the capitalization rate.

Example 2.

Let’s tweak the cost of equity.

Year 11 owner earnings $100.

Cost of Equity = 2%

Growth Rate = 1%

Terminal value: $100/ (.02-.01) = $100/1% = $100 * 100 = $10,000.

In this instance, the capitalization rate is 1%.

$2000 versus $10000. Which terminal value should I use? Time to call my goldfish.

The valuation analysis is very heavily dependent on the terminal value, which itself is extremely sensitive to the capitalization rate, which itself is based on assumptions ten years out for which we have little or no evidence today.

The calculation is riddled with speculation. Change your assumptions, and you get wildly different results. Bruce Greenwald, an author mentioned in the Reference Section, discusses this issue at length.

Most DCF capitalization rates end up being around 3%, equivalent to a multiplier of 33.3.

To be conservative, I use a capitalization rate of 7% (or 10% to be even more conservative). Purists may recoil in horror because my approach fails to account for thee specifics of each company’s situation. Yes, my approach is crude. However, in the end, it adds to my margin of safety.

After You Buy

I have seen neophyte value investors say something like, “I bought the stock last month. Why hasn’t it gone up?” Short answer: it takes time.

Here are some possible reasons:

Because the world doesn’t care what you think or do.

If you are an investing genius, it is going to take some time for the world to catch up.

You are no investing genius

The company doesn’t execute as you thought—though it usually will take you a few years to figure the company is run by a bunch of boneheads..

You are wrong. Your analysis or thesis is wrong. (Join the club.)

My assertion (nothing more) is that you should not expect prices to adjust in less than three years. My understanding is three years is the time frame Peter Lynch had in mind when he bought a security. Of course, you need to monitor your company’s progress against your investment thesis.

Continue to Next Post

When To Sell

Ideally, never. Anne Schreiber rarely sold, and she seem to do all right. My style is to invest in reasonably priced compounders which grow into perpetuity and always have an intrinsic value above their current stock price. That’s a nice idea, but such a company is rare. To get a sense of this, look at the lists of Fortune 500 companies in 2000 and in 2…